The ideal gallery subtracts from the artwork all cues that interfere with the fact that it is ‘art’. The work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself. This gives the space a presence possessed by other space where conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values. Some of the sanctity of the church, the formality of the courtroom, the mystic of the experimental laboratory joins with a chic design to give a unique chamber of aesthetics.

Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, University of California Press, London, 1986

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

Monday, March 23, 2009

The 'Doppelcharakter'

“The artwork is a commodity of a special kind. It is considered unique, and it is split between its assumed symbolic value and its market value. The peculiarity of its Doppelcharakter relies on the fact that it can have a price only because it is presumed to be priceless- which is true to a certain degree, as what is at stake in artworks cannot be reduced to a price. Collectors’ motives can’t be reduced only to speculation. They want the market value to increase, yes, but their motives are hybrid. They want the symbolic value as well.”- Isabelle Graw, Artforum April 2008, ‘Art and Its Markets- A Round Table Discussion’

http://www.artforum.com/inprint/id=19746&pagenum=1 (login required)

Image, Medium, Body, A New Approach to Iconology by Hans Belting

Link to AAARG.org article

The idea of linking the physical images with the mental image. The old cultures of practice of consecration (religious for example) rituals that changed an object into something powerful therefore creating icons of worship.

The idea of linking the physical images with the mental image. The old cultures of practice of consecration (religious for example) rituals that changed an object into something powerful therefore creating icons of worship.

Sigmar Polke/ Fetish definitions

fetish-

fetish--an inanimate object worshipped for its supposed magical powers or because it is considered to be inhabited by a spirit

-a course of action to which one has an excessive and irrational commitment

- a form of sexual desire in which gratification is linked to an abnormal degree to a particular object, item of clothing, part of the body, etc…

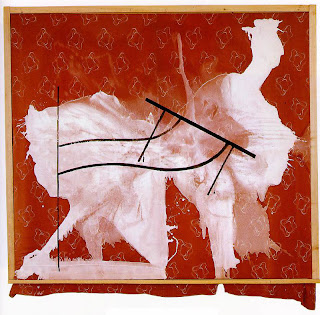

(www.encyclopedia.com)Tables Turning Sigmar Polke (1981)

n the 1970s, in his farmhouse near Dusseldorf, Polke experimented with photographic dark-room techniques, deliberately ignoring the standard rules: ‘dropping the wrong chemicals onto the paper, turning on the light during development, brushing the developer on selectively, using exhausted fixer’.6 The ‘mistakes’ turned into inventive techniques: for example, he started to fold the paper during development because the trays were too small for larger prints, but the welcome effect was that the image became obscured by blossoming chemical stains along the folds. This fitted well with Polke’s psychedelic exuberance and interest in spatial juxtaposition (the flat, folded paper producing the other-worldly clouds), but it also harked back to the early days of photography, revisiting a time when the new technology was considered a medium in more than one sense – as a means to summon ghosts. Exposing surfaces to experimental mixtures of substances and light fed into Polke’s painting, further fuelled by his ambitious research into ancient and new pigments and paint during trips to Australia and South-east Asia; just in time for the return of painting in the ’80s.

Made on the back of all this, Tischerücken (Table Turning, 1981) has been described as a breakthrough painting, although it actually exemplifies several kinds of literal and metaphorical breakthroughs. There is the brownish-red furnishing fabric, which acts as the ‘canvas’ and slips through the lower end of the dark wooden frame it is stretched on like a fastened tablecloth (which, with its repetitive pattern of a gently curved and closed form, it could well be). The lower horizontal bar of the frame, however, is mounted in such a manner that it juts out from the wall as though it was a windowsill with a curtain stuck under it, letting the painting flip between the table and window association, between object and image. This movement is reflected by a large irregular puddle of white paint spilled on the cloth, apparently applied when the painting was horizontal, so that the oozing of the paint could be controlled by jacking its sides up or down; it is also reflected by the fact that on top of this puddle there is the black outline of a ‘flying’ table.

The tables in this work are, of course, those used for a séance, and the white spills directly reminiscent of ectoplasm.7 Yet the séance table was also Karl Marx’s oft-cited metaphor for the strange machinations of commodity fetishism: for as soon as an ordinary wooden table ‘steps forth as a commodity, it is changed into something transcendent. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than “table-turning” ever was.’8 Polke – pointedly at a time when painting resurged as a particularly sought-after commodity – seemed to juggle these different levels of meaning at once, while making sure that none of them became too securely fixed.

Frieze Issue 110 October 2007 by Jorg Heiser

Eagleton's Ideology of the Aesthetic

‘What one ought to do can no longer be deduced from what, socially and politically speaking, one actually is; a new distribution of discourses accordingly comes about, in which a positivist language of sociological description breaks loose from ethical evaluation. Ethical norms thus float free, breeding one or another form of intuitionism, decisionism or finalism. If one can return no social answer to the question of how one ought to behave, then virtuous behaviour, for some theorists at least, must become an end in itself… the work of art is now becoming ideologically modelled on a certain self-referential conception of ethical value.’

Don Thompson: Economics of Contemporary Art

Book by the economist Don Thompson, The $12 million Stuffed Shark.

Book by the economist Don Thompson, The $12 million Stuffed Shark.“Money itself has little meaning in the upper echelons of the art world-everyone has it. What impresses is ownership of a rare and treasured work such as Jasper Johns’ 1958 White Flag. The person who owns it ( currently Michael Ovitz in Los Angeles) is above the art crowd, untouchable. What the rich seem to want to acquire is what economists call positional goods; things that prove to the rest of the world that they really are rich."

But art distinguishes you. A large and recognizable Damien Hirst dot painting on the living room wall produces: ‘Wow isn’t that a Hirst?’

Fred Hirsch: Positional Goods

Positional goods are products and services whose value is mostly (if not exclusively) a function of their ranking in desirability, in comparison to substitutes. The extent to which a good’s value depends on such a ranking is referred to as its positionality. The term was coined by Fred Hirsch in 1976.

Hirsch, Fred. The Social Limits to Growth, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London

Other terms of note are Conspicuous consumption, a term used to describe the lavish spending on goods and services acquired mainly for the purpose of displaying income or wealth. Invidious consumption, a necessary corollary, is the term applied to consumption of goods and services for the deliberate purpose of inspiring envy in others.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)